Field Report: The Chalk Creek Hieroglyphs

A report of my latest adventure in the backroads of the West.

Wildfire haze taints the wide open sky as I arrive in Fillmore mid morning. The main drag is wide and deserted. There are no stoplights.

Located in the desiccated heart of Utah, the small town was ordered built by Brigham Young with the intent of serving as the Territory’s capital. It did so for about five years before the government moved to the real seat of power in Utah: Salt Lake City.

The absurdly wide streets of the town betray the old pioneer optimism and a vision of a bustling city at the foot of the mountains. But unlike Salt Lake City, Fillmore never grew up. It just got old. Most of the houses are faded and weather beaten. The grass is knee high, golden, and ready to catch a spark.

I pull over in front of the historic state house to check my map. If I have time, I’ll come back. But first, the hieroglyphs.

I learned about the Chalk Creek Hieroglyphs by chance, scrolling around for points of interest in Google maps. The Wikipedia page was sparse. One of the books it referenced—a resource for Utah treasure hunters—was available at the university library, but it didn’t provide much more than a black and white picture of the site. All I could find is that no one knows for sure what the mysterious symbols carved into the mountain mean, and they have not lead to riches thus far. Being less than two hours from home and not too far off the beaten path, it’s perfect for a weekday excursion.

I drive uphill, past the edge of town. The wine-dark road is newly paved, and it curves past pristine and abandoned houses alike. After a couple miles, I rattle over a cattle guard and onto a gravel road. Doves alight from the white cliffs that lend name to the canyon. A covey of quail kick up a cloud of dust as they dart across the road.

I find my next turn off. The track is steep and rocky and a bit more of a challenge than I’m up for in the family SUV. I park in a turn out beneath craggy cottonwoods that drink from the cool, clear creek.

I put on my pack and a Panama hat that I hope will be seen as friendly by the spirits of Spanish miners who haunt these hills and I start walking.

The air is sweet with sun-heated juniper. Clusters of berries weigh down the boughs, and exposed roots contort down into the dusty soil. The initial climb is steep, but the road levels out atop the ridge. Tire tracks cover the rutted road; none are fresh. I have the mountain to myself. This close to midday, and with temperatures climbing, my only companions are the grasshoppers that break cover to hop from one sun-soaked rock to another. At a fork, I turn right, following a sign to my destination. This spur of road dead ends at couple lengths of rail fence in front of a rocky outcropping. I have arrived.

Two faded interpretive panels installed by the forest service stand behind the fence. I ignore them, not wanting my initial impression of the site to be tainted, and walk up to the piled stones. The stacked boulders frame the opening of a cave. It is reminiscent of the entrance to an old-world barrow tomb, and I wonder whether this is mere natural occurrence. My eyes are drawn to the dark recess. I am compelled to enter.

The Chalk Creek Hieroglyphs were discovered in 1939 by a local prospector, Clifford Purcell. The symbols were encrusted with lichen and a providential sunbeam highlighted the location for the man as he was scouting. In subsequent decades, news of the find spread. Believing that the writings indicated the location of hidden ancient scripture, Mexican archeology enthusiast Jose Davila led an excavation effort from 1965 through 1969. During this time, three local men, including the claim owner, descended into the diggings and succumbed to toxic gases.

Within the cave, I see initials carved into the walls. I stoop as I move forward . The chamber is not very deep and ends in a small room filled with pack-rat droppings. It is possible that boulders block more tunnel, but it is not obvious. Seeing no signs of the hieroglyphs, I back out of the cave. I look around the entrance and spot the carvings on a panel above the entrance.

The symbols are arrayed in four rows; the top row having only one symbol: a skull in profile, mouth agape. Each of the other three rows has several symbols, some of which are recognizable as objects. Head, hand, cross. Other symbols are more abstract. Parallel lines, circles, triangles, rectangles.

I retreat to find a good place to scramble up to get a closer look. The summer-drab scene is splashed with bright green. Sunflowers—no doubt planted on the solstice by secret devotees of the sun god worshiped here—grow in loose soil among the thistle. I flank the plants and find a series of ledges to climb. The rough rock is embedded with quartz and other shining minerals.

Specters linger in my periphery, unwilling or unable to make themselves known. Perhaps they are connected to this place by oath or circumstance, or maybe they were just drawn to the energy here while wandering the liminal wastes. I scramble around the site and take pictures under their watchful eyes. I sense no malice from the spirits, but as I finish I know that it is time for me to go.

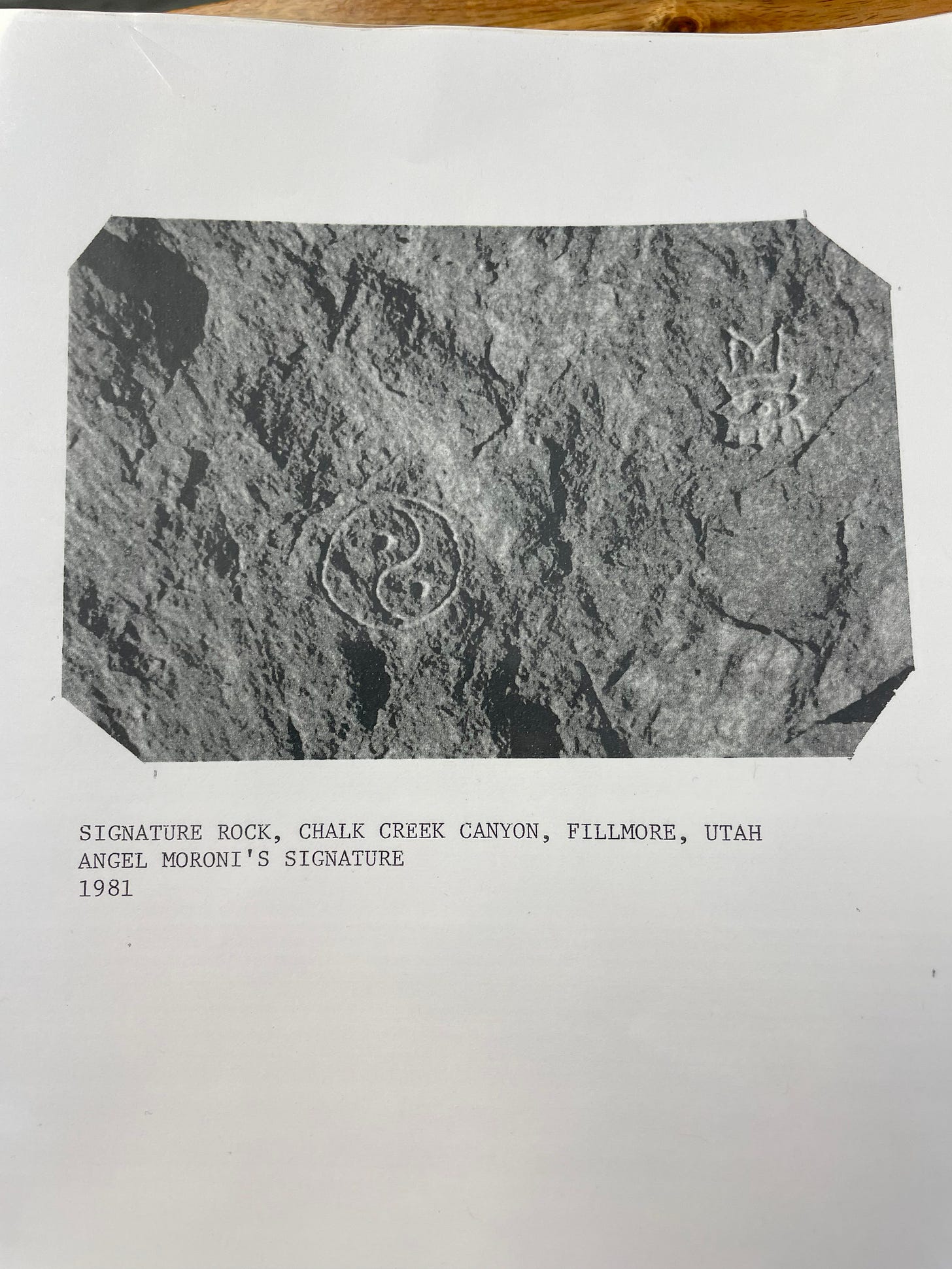

Coming back down out of the canyon, I stop by the forest service office located on a shady corner of the main drag. It is home to an additional artifact. In full compliance with federal weapons laws, I enter the building and am greeted by two star-struck women. I ask them about the other hieroglyphs that were on a boulder that fell off the original site during excavations in the 60s. They produce a black and white copied photograph of a carved yin yang and a stylized eye. The older woman tells me about them.

“These are the symbols. This one,” she points to the eye, “is called the Angel Moroni signature. You can see the ‘M’ right there. You can keep this copy if you want.”

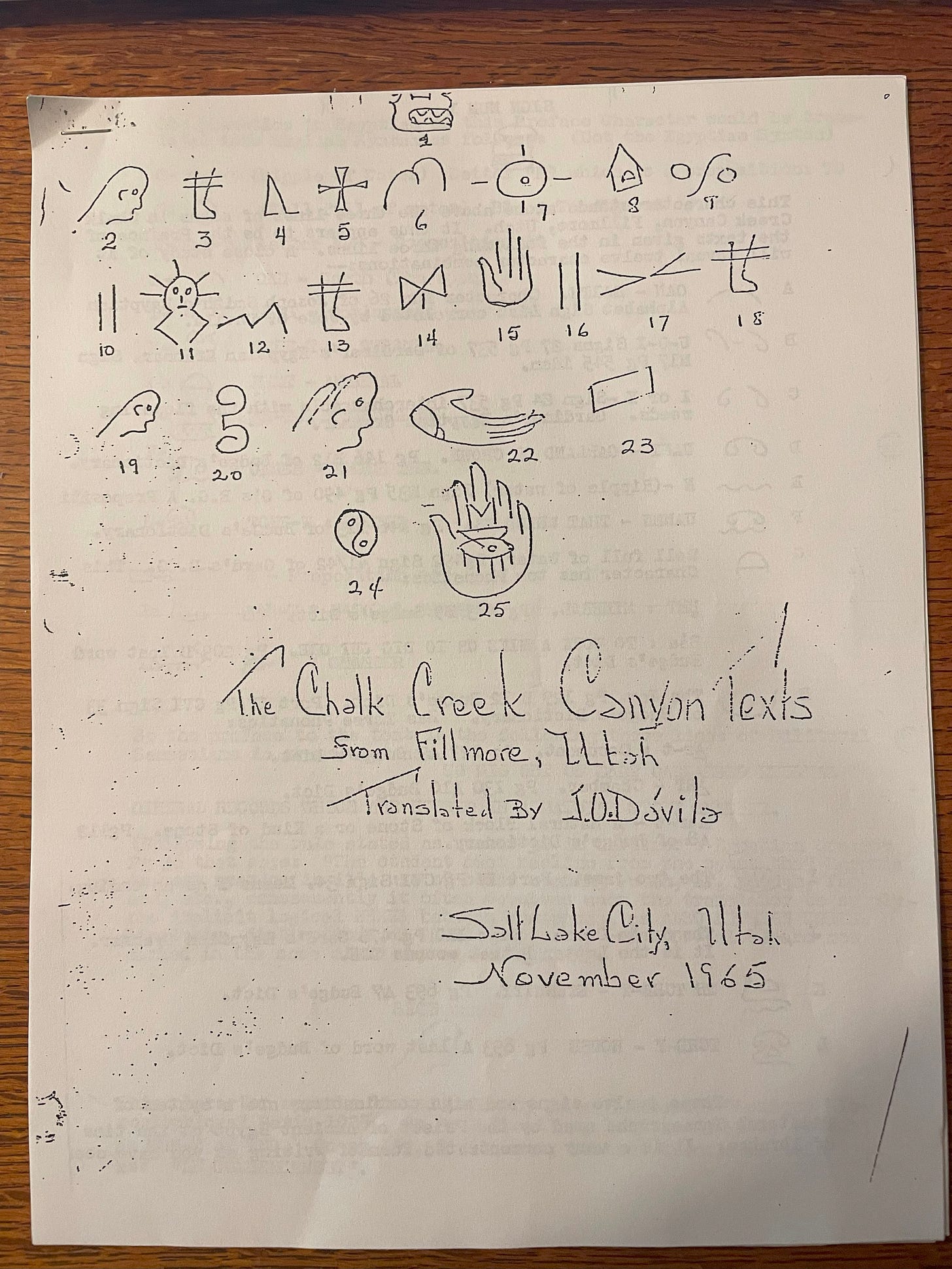

I am quick to accept, and sensing in me no guile, they also offer me a barely legible copy of Davila’s detailed 1965 translation of the full panel of hieroglyphs. Thanking them, I accept the papers and a recommendation for a good lunch spot and turn to leave.

“The boulder is just around back,” the younger woman says. “They built an awning over it.”

Outside, I take a look at the rock. The carvings are faint. When initially discovered, the “signature” glyph was painted with a red hand print. No trace now remains.

At Cluff’s Carhop Cafe, I order a blue cheese bacon burger, onion rings, and an Oreo shake. I also get a Diet Coke in their largest cup. The waitresses here are pleasant; some middle-aged, some younger. Just like waitresses countrywide, all are tattooed.

While I wait for my food at one of the tables squeezed into the small indoor dining room, I look through my photographs and the documents procured from the forest-service matron. The translation is imaginative. The translator—citing Gardiner and Budge, among others— claims the hieroglyphs to be Egyptian and places the writing in the context of the Book of Mormon. He must have caused quite a stir in this small town sixty years ago. The treasure it promised in the translation is additional ancient records written on metal plates.

My food arrives, and I eat my fill. The old-timers at the table next to me talk about country life in accents once foreign to Deseret. Maybe they are transplants from the south. Maybe they’ve just listened to too much George Strait and watched Lonesome Dove one time too many.

My thoughts wander from the hieroglyphs to the people of this town—my distant cousins—and culture we failed to inherit. We have made ourselves indistinct from the people who live anywhere else the signal beams. Fillmore may not be a time capsule, the foreign country I was half expecting, but the past exists somewhere, and its denizens still have something to say to those with ears to hear.

I say thanks to the ladies as I drop off my tray on the way out the door.

“Can I get you a refill?” asks the brunette at the register.

“Thanks. I was about to ask for one. Diet Coke.”

“I know.” She smiles.

It’s well over 100° when I get back on the road. The afternoon monsoon clouds rise in the steel-blue sky; forming ex nihilo, billowing, white.

This was fascinating and very well written. Keep it up!